March 1, 2016

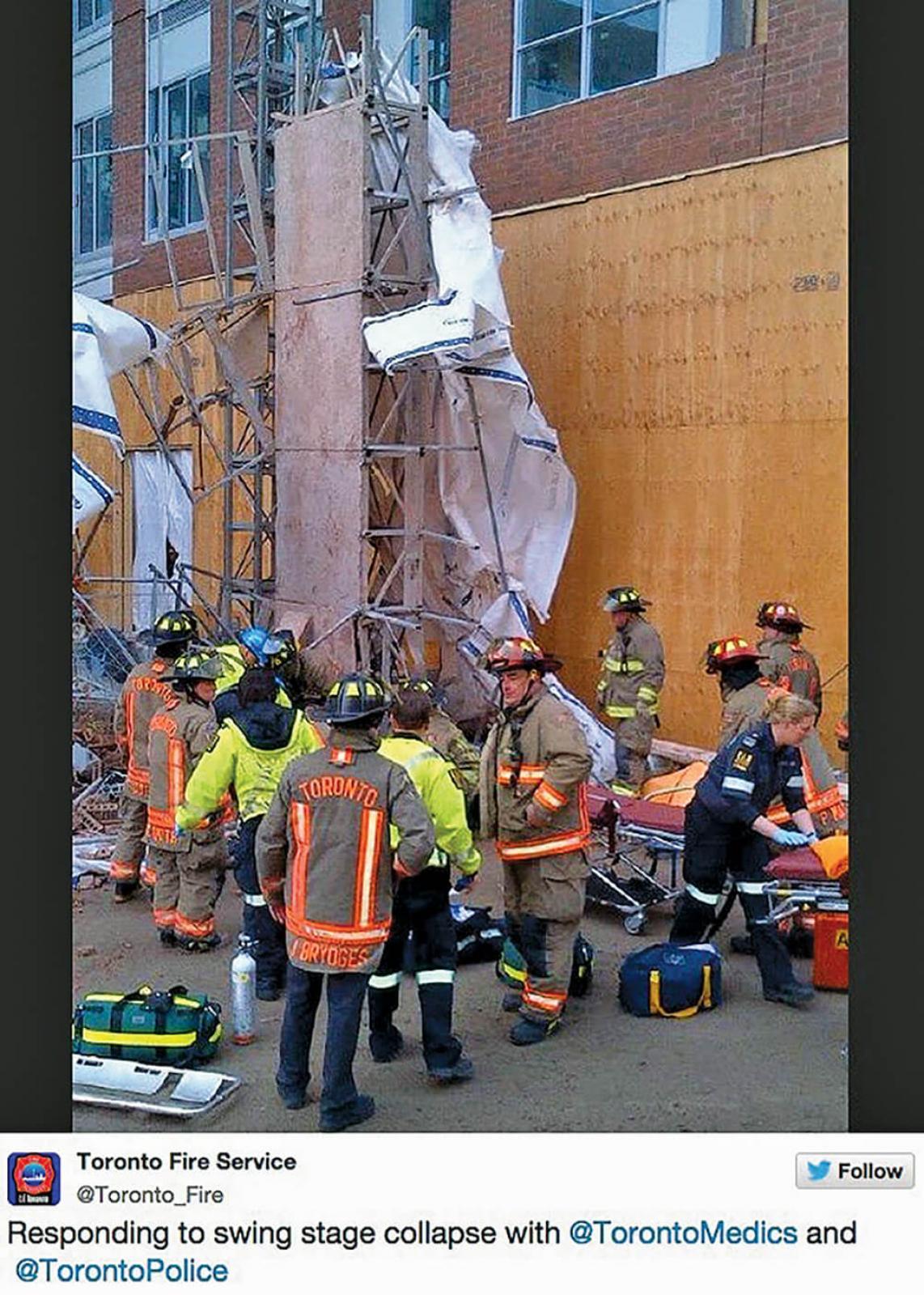

Canadian employers must know that negligence can result in criminal prosecution and jail time — as happened to Metron Construction after this workplace accident.

Workplace accidents: a sobering case

BY ROB KENNALEY In the fall of 2009, Metron Construction was repairing the concrete balconies of an 18-story apartment building in Toronto. On Christmas Eve of that year, six Metron workers (including a foreman) boarded the swing stage, although lifelines were in place for only two. As a matter of Occupational Health and Safety legislation, of course, every person working on a swing stage must be protected from falls – which in this case meant each worker was to be attached to a separate lifeline. On the day in question, one worker attached his lanyard to one of the lines, while none of the others (including the foreman) tied-down to the other. The platform collapsed, sending four of the five workers not tied down to their deaths. One worker miraculously survived the fall, as did the tied-down worker.

In the fall of 2009, Metron Construction was repairing the concrete balconies of an 18-story apartment building in Toronto. On Christmas Eve of that year, six Metron workers (including a foreman) boarded the swing stage, although lifelines were in place for only two. As a matter of Occupational Health and Safety legislation, of course, every person working on a swing stage must be protected from falls – which in this case meant each worker was to be attached to a separate lifeline. On the day in question, one worker attached his lanyard to one of the lines, while none of the others (including the foreman) tied-down to the other. The platform collapsed, sending four of the five workers not tied down to their deaths. One worker miraculously survived the fall, as did the tied-down worker. Passed in March of 2004, Bill C-45 established new legal duties for workplace health and safety, and imposed serious penalties for violations that result in injuries or death. The bill provided new rules for attributing criminal liability to organizations, including corporations, their representatives and those who direct the work of others. It added section 217.1 to the Criminal Code of Canada, which provides: “Everyone who undertakes, or has the authority, to direct how another person does work or performs a task is under a legal duty to take reasonable steps to prevent bodily harm to that person, or any other person, arising from that work or task.”

Responsibility for prevention

Metron had retained a project manager for the project, who had “the authority to direct how another person does work” and was thus required pursuant to s. 217.1 of the Criminal Code “to take reasonable steps to prevent bodily harm to that person…arising from that work…” The project manager was charged personally with five counts of criminal negligence and at trial, the Court found the project manager was aware, well in advance of the stage’s collapse (perhaps for as long as eight hours), that there were only two lifelines available for the six workers on the stage.The court rejected the project manager’s argument that he had discharged his duty under s. 217.1 by asking the foreman about the absence of the lifelines. The Court also rejected the argument that because the workers who boarded the stage were experienced and aware of the need for fall protection, the project manager should be absolved of responsibility. In addition, the court rejected the argument that the project manager should be partially absolved because he did not coerce the workers to ignore safety protocols.

In this regard, the Court held that to even partially absolve the project manager on the basis of the victims’ awareness of the danger or the absence of overt coercion would ignore the reality that a worker’s acceptance of dangerous working conditions is not always a truly voluntary choice. It would also tend to undermine the purpose of the duty imposed by s. 217.1 of the criminal code, which is to impose a legal obligation in relation to workplace safety on management.” [Emphasis original]

The court further stated that this is not a case in which “liability for criminal negligence is based on a failure [to recognize] an obvious and serious risk to the lives and safety of his workers. Rather, it is a case where he did [recognize] the risk but decided that it was in Metron’s interest to take a chance. As a consequence of his decision to put Metron’s interests ahead of his duty to protect the safety of the workers under his authority, four men died and a fifth suffered grievous harm.”

The court found the project manager guilty on all five counts of criminal negligence causing death and bodily harm and stated that once he became aware that fall protection was lacking, there was a duty to take steps to rectify the situation under s.217. 1 of the criminal code.

Imprisonment reflects seriousness

The project manager is 40 years old, had no prior criminal record and is married with three young children. The court found him to be of good character, hardworking, devoted to his family, involved in his community, remorseful and quite unlikely to commit further criminal offences of any kind. It was not even suggested that a term of imprisonment was required to deter the project manager from committing further offences. Notwithstanding this, the court held (and the defence agreed) that a term of imprisonment was necessary to adequately denounce the criminal conduct and to deter other persons with authority over workers in potentially dangerous workplaces. The project manager was sentenced to 3½ years in prison.The moral in this story hardly needs to be summarized here: work safe; prioritize safety; meet your occupational health and safety obligations; have proper policies in place to meet these obligations, and have policies in place to make sure those policies are being followed. Never look the other way, and make sure your workers and subcontractors don’t either; have zero tolerance for those that do.

Robert Kennaley of McLauchlin & Associates practices construction law in Toronto and Simcoe, Ont., and speaks and writes regularly on construction issues. He can be reached for comment at 416-368-2522 or at kennaley@mclauchlin.ca. This material is for information purposes and is not intended to provide legal advice in relation to any particular fact situation. Readers who have concerns about any particular circumstances are encouraged to seek independent legal advice in that regard.